The Sicilian cart, from vehicle to work of art

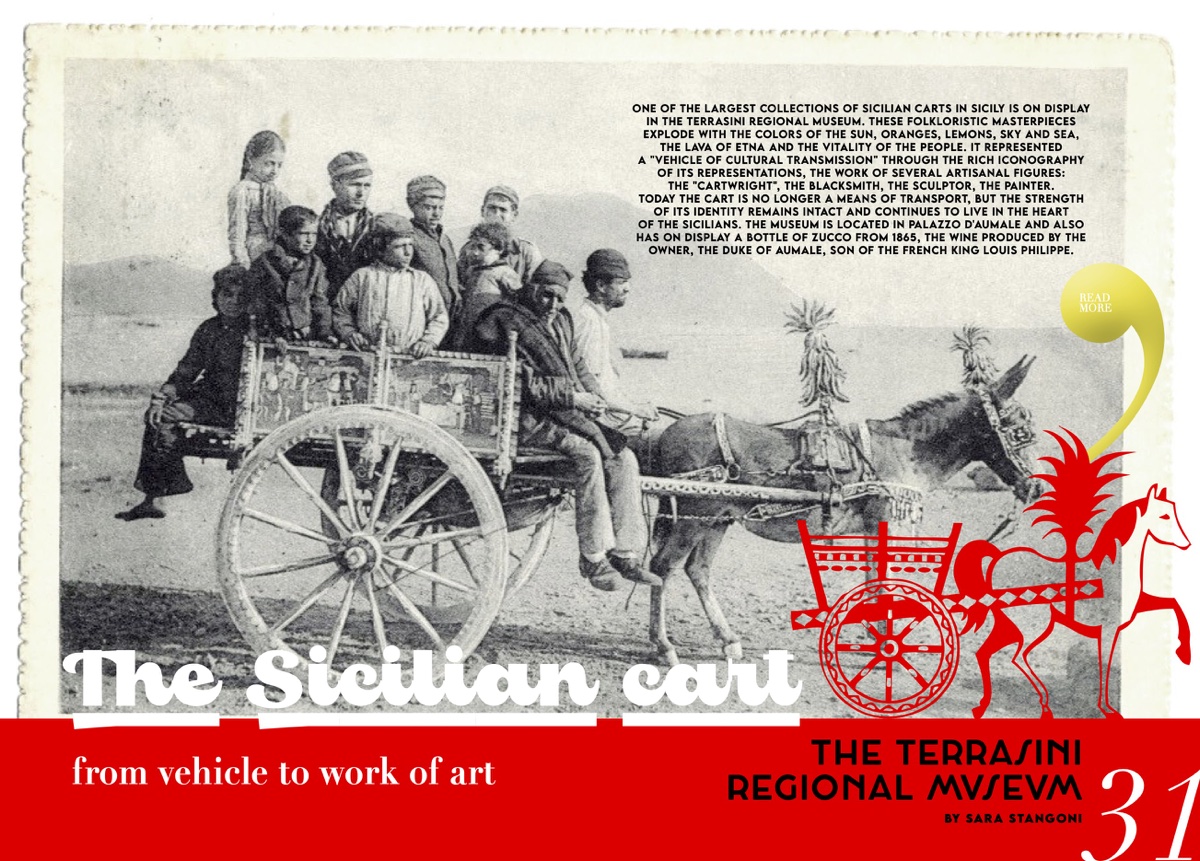

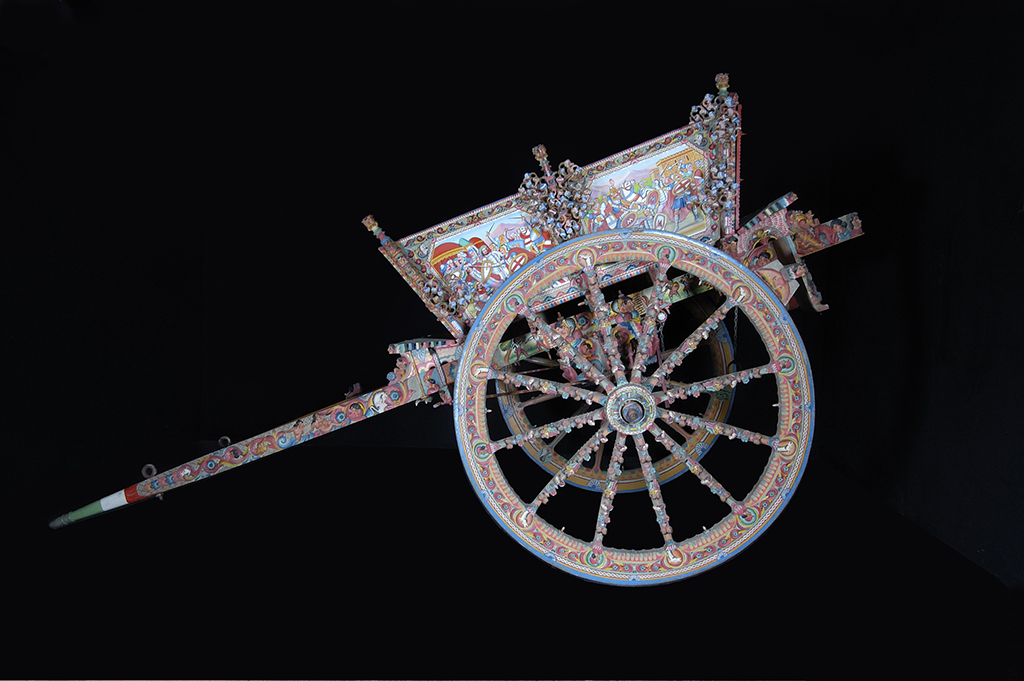

One of the largest collections of Sicilian carts in Sicily is on display in the Terrasini Regional Museum. These folkloristic masterpieces explode with the colors of the sun, oranges, lemons, sky and sea, the lava of Etna and the vitality of the people. It represented a “vehicle of cultural transmission” through the rich iconography of its representations, the work of several artisanal figures: the “cartwright”, the blacksmith, the sculptor, the painter. Today the cart is no longer a means of transport, but the strength of its identity remains intact and continues to live in the heart of the Sicilians. The Museum is located in Palazzo d’Aumale and also has on display a bottle of Zucco from 1865, the wine produced by the owner, the Duke of Aumale, son of the French king Louis Philippe.

When Guy de Maupassant landed in Palermo in the spring of 1885, he was fascinated. He wrote in his travel diary: “These carts, small square boxes, perched high on yellow wheels, are decorated with simple and curious paintings, which represent historical facts, adventures of all kinds, meetings of kings, but mainly the battles of Napoleon I and the Crusades; even the spokes of the wheels are decorated”.

I was 10 years old the first time I rode a Sicilian cart. And I felt the same childish wonder: a fairytale vehicle that emanated colorful poems and fantastic stories.

The cart emerged in Sicily with the roads, since before then trade and transport on the island took place by sea or on the back of a mule. It was only in 1778 that the Sicilian Parliament approved an allocation of 24,000 scudi for the construction of a road network in Sicily. They were roads made up of dirt tracks, with hills and sharp turns. A vehicle capable of tackling those routes was required: the cart, with its high wheels, proved to be the most agile means of transporting people and materials. Today it is certainly the best known and most characteristic element of Sicilian folk art.

The Terrasini Regional Museum of Natural Sciences and the Cart looks out over the Praiola beach, bringing Sicily into its rooms, between the blue of the Tyrrhenian sea and the bright blue of the sky. The palace takes its name from Henri d’Orleans, Duke of Aumale, son of the French king Louis Philippe and Maria Amelia of Bourbon. It was acquired by the French duke in the mid-nineteenth century as a storage facility for his wine. He chose the wild and mineral rich lands of Terrasini, where the fresh breeze from the sea blows everyday, to produce Zucco. A bottle from no less than 1865 can be found in the Museum, a donation from Charles Dossi and Silvio Ruffino.

The visit begins spectacularly with the reconstruction of a section of the Kirenya ship full of stowed amphorae. The archaeological section presents artefacts that come from the cargo of the wrecks of Roman cargo ships and from other underwater sites around Terrasini and Trapani. The naturalistic section, on the other hand, brings together the entomological, ornithological, malacological and mammalian collections. But the undisputed stars of the museum are the Sicilian carts, with one of the richest collections in terms of theme and type.

Mimmo Targia has been the director of the museum since last October and he talks about his enhancement policies with a touch of pride. “We have started the procedure for the recognition of the cart as a part of Unesco heritage, as is already the case for the work of the Sicilian puppets. I also intended to involve the Catania Academy of Fine Arts and entrepreneurial figures, because the Sicilian cart is the authentic expression of the Sicilian people and of that age-old culture that nourishes its wonderful color palette, even if it originated at the end of the eighteenth century. It is an excellent time for us and we must promote the excellence of this museum”.

The cart is a work of art in motion with the contribution of several artisanal figures: the “cartwright”, the blacksmith, the sculptor, the painter. In a time when books and knowledge were only for a few, the carts were bearers of messages and walking manifestos of the historical narrative. The main function of painting was to protect the wood from the elements. This combined with the magical-religious function of warding off negative forces and ensuring prosperity for the owner and his family who “traveled” from street to street, together with advertising, especially for carts that carried out commercial activities.

But what subjects do we find on these small chests? The genres depicted with laborious craftsmanship and creativity are diverse: historical-chivalrous, legendary-fairytale, devout, musical and realistic. Sacred images of St. George and the dragon and of the Holy Family are always painted, as well as sculpted, on the parts most at risk of breaking; in particular we find them on the lace of the spindle box (part of the cart trailer), the most difficult and delicate part according to the craftsmen. Here therefore, the lives of the saints and the deeds of the sovereigns, the battles of Napoleon and the Sicilian vespers, the inevitable stories of the paladins and Charlemagne drawn from the work of Sicilian puppets, all appear on the various carts. The cart was divided into four types based on the area of origin, with different shapes and decorations, in particular on the spindle case and the side panels: the Palermo, Castelvetranese, Trapani and Catania types.

Today there are few “cartwrights” left, but they work proudly. They know they have inspired great artists such as Renato Guttuso who, from an early age, frequented the workshop (“putìa” in Sicilian) of the Ducato brothers from Bagheria. “They were my first masters of color” he declared and transposed figures and chromatic combinations into his painting. “In the Museum – concludes the director Targia – we are lucky enough to have on display some carts from the prestigious ‘putìa’ of Corso Butera, located among other things in front of Villa Cattolica, where Guttuso himself is buried. Today Michele Donato’s heirs work with Dolce & Gabbana and the cart is never missing from their sets”.

Sicilian carts are a wonderful time machine, able to guide us into history and retrace it, passing from one period to another. Maybe humming: “Oh, what a beautiful job to be a carter, going here and there”, as Alfio did in Giovanni Verga’s Cavalleria Rusticana.